The following article from the original Army Motors illustrates in brief the Army’s process for obtaining a vehicle. It points toward the contrary notion that the military went to a manufacturer not knowing what it wanted. In truth, the Army (represented by engineers, military and civilian) went to the manufacturer to iron out details and specifications. This article, dating from May 1940, deters from the idea that American Bantam Car Company primarily designed and built the worlds’ first jeep. While this article does not specifically name the jeep it does give you the procurement concepts used for the purchase of trucks. There is little doubt that the little car company played a major role in proving the worthiness of the concept – by building a “hand made model of the proposed vehicle”. Because the model was deemed successful, the Army ordered Bantam to construct another 69 jeeps in accordance with contract 393-41-9 for 62 two-wheel steer and 8 four-wheel steer pre-standardized jeeps. However, the first builder of the jeep was not successful in its bid for a production contract for the standardized jeep – losing out to Willys as low bidder. Later Ford was awarded contracts as a second supplier of the standardized jeep leaving Bantam to build other items for the war effort.*

Private Jones was rolling one of the latest trucks down the highway.”Nice buggies these new ones”, he thought, “the front driving axle seems to keep them moving along right smartly. They don’t seem to sway so much either, must be built a bit closer to the road. The Army going streamlined, eh? Not a bad idea at all – had to use a ladder to climb into some of those old babies.”

The rest of the convoy was stretching ahead, and as he glanced back now and again he saw the maintenance truck swinging around the curves behind him. Whoa! Something going wrong up ahead – he could see the vehicles gradually bunching up like a closingaccordionn as they slowed down and stopped. Some kind of a parley was going on up front by the looks of things; after a few minutes the convoy

The following article from the original Army Motors illustrates in brief the Army’s process for obtaining a vehicle. It points toward the contrary notion that the military went to a manufacturer not knowing what it wanted. In truth, the Army (represented by engineers, military and civilian) went to the manufacturer to iron out details and specifications. This article, dating from May 1940, deters from the idea that American Bantam Car Company primarily designed and built the worlds’ first jeep. While this article does not specifically name the jeep it does give you the procurement concepts used for the purchase of trucks. There is little doubt that the little car company played a major role in proving the worthiness of the concept – by building a “hand made model of the proposed vehicle”. Because the model was deemed successful, the Army ordered Bantam to construct another 69 jeeps in accordance with contract 393-41-9 for 62 two-wheel steer and 8 four-wheel steer pre-standardized jeeps. However, the first builder of the jeep was not successful in its bid for a production contract for the standardized jeep – losing out to Willys as low bidder. Later Ford was awarded contracts as a second supplier of the standardized jeep leaving Bantam to build other items for the war effort.*

Private Jones was rolling one of the latest trucks down the highway.”Nice buggies these new ones”, he thought, “the front driving axle seems to keep them moving along right smartly. They don’t seem to sway so much either, must be built a bit closer to the road. The Army going streamlined, eh? Not a bad idea at all – had to use a ladder to climb into some of those old babies.”

The rest of the convoy was stretching ahead, and as he glanced back now and again he saw the maintenance truck swinging around the curves behind him. Whoa! Something going wrong up ahead – he could see the vehicles gradually bunching up like a closingaccordionn as they slowed down and stopped. Some kind of a parley was going on up front by the looks of things; after a few minutes the convoy

started snaking ahead again slowly. As Jones drove up to the halting place he saw the rest of the convoy swinging sharply to the right, off the highway. Jones was waved on by a guide who shouted, “Detour – take it easy – bad goin’!” as he passed him. “Good enough”, thought Jones, “we will see what this baby can do when the goin’ gets tough”.

It got tough so rapidly that Jones stopped complaining about other people’s business and concentrated on his own business of keeping the truck in the middle of the heaving gumbo track that was worse than a cross country trail. Whoomp! down she went into a hole that probably had been a bump when the first truck hit it but that felt like a shell crater now. Uuhn! she stuck. The air in the cab got hot as Jones gave his opinion of the truck manufacturer. . .”Why in ‘ell don’t they lift these buggies another four inches…you’d think they was making baby carriages instead of Army trucks. . .they belly down and stick in the mud like a turtle…with nineteen million bucks to spend you’d think they’d do something about this. . .”

started snaking ahead again slowly. As Jones drove up to the halting place he saw the rest of the convoy swinging sharply to the right, off the highway. Jones was waved on by a guide who shouted, “Detour – take it easy – bad goin’!” as he passed him. “Good enough”, thought Jones, “we will see what this baby can do when the goin’ gets tough”.

It got tough so rapidly that Jones stopped complaining about other people’s business and concentrated on his own business of keeping the truck in the middle of the heaving gumbo track that was worse than a cross country trail. Whoomp! down she went into a hole that probably had been a bump when the first truck hit it but that felt like a shell crater now. Uuhn! she stuck. The air in the cab got hot as Jones gave his opinion of the truck manufacturer. . .”Why in ‘ell don’t they lift these buggies another four inches…you’d think they was making baby carriages instead of Army trucks. . .they belly down and stick in the mud like a turtle…with nineteen million bucks to spend you’d think they’d do something about this. . .”

Nineteen million bucks is right, Jones, but even with that pile of dough you can’t walk into a truck dealer, plunk down your money and walk out with a 7 1/2 ton (6×6) prime mover for anti-aircraft artillery. Even ordinary commercial trucks are not produced and sold like passenger cars; that is, there is no one particular model regularly produced and stocked by a manufacturer or his dealer. Trucks are assembled “tailor made fashion” to meet the purchasers’ needs as to type

of body, length of chassis, combinations of transmissions and axles and even types of engines. Besides these usual commercial variations, the Army requires still further deviation from standard commercial chassis in such major features as bodies, a11-wheel driving axles and dual rear axles for six-wheel vehicles.

Before the Army can even starts thinking of issuing invitations for bids on new vehicles, it has to decide what kind of vehicle it wants. Sounds easy, eh? Just sit down and order a truck like a new pair pants. Well, it isn’t, Jones – not at all. The using arms and services; the Quartermaster Corps and the manufacturer must cooperate in drawing specifications for vehicles that are not only satisfactory to all concerned, but that can be produced economically. That is as difficult as dividing two doughnuts between three hungry kids. For example, the Cavalry might desire a 2 1/2 – ton cargo truck with a top road speed in high gear of forty-five miles per hour, whereas the Field Artillery might want the same general type of vehicle with a top road speed of only thirty-five miles per hour and with a proportionately greater pulling power; or several using arms and services might be satisfied with a certain type of vehicle but one of them might require a special wheel spacing to permit the use of traction devices which are of no particular value to the other users. A compromise between these conflicting desires must be found before a vehicle acceptable to all can be produced.

With the nineteen million dollars that Jones was complaining about, the Army is purchasing approximately 16,000 vehicles of 32 different types. The specifications in the invitations for bids covering each type of vehicle or unit average twenty-five pages, and each page contains about 10 items or a total of approximately 2,500 items in each invitation.

If the specifications call for any basic changes in chassis, the manufacturer, after the complete engineering layouts have been made on paper, must build a hand made model of the proposed vehicle. These models cost about $80,000 each, and not infrequently several models must be made before a satisfactory vehicle is obtained. If the design seems satisfactory, it costs the manufacturer anywhere from half million to a million and half dollars to make the necessary changes in the factory equipment, tools, dies, jigs, etc., in order to roll the vehicle off the delivery line by mass production methods.

Nineteen million bucks is right, Jones, but even with that pile of dough you can’t walk into a truck dealer, plunk down your money and walk out with a 7 1/2 ton (6×6) prime mover for anti-aircraft artillery. Even ordinary commercial trucks are not produced and sold like passenger cars; that is, there is no one particular model regularly produced and stocked by a manufacturer or his dealer. Trucks are assembled “tailor made fashion” to meet the purchasers’ needs as to type

of body, length of chassis, combinations of transmissions and axles and even types of engines. Besides these usual commercial variations, the Army requires still further deviation from standard commercial chassis in such major features as bodies, a11-wheel driving axles and dual rear axles for six-wheel vehicles.

Before the Army can even starts thinking of issuing invitations for bids on new vehicles, it has to decide what kind of vehicle it wants. Sounds easy, eh? Just sit down and order a truck like a new pair pants. Well, it isn’t, Jones – not at all. The using arms and services; the Quartermaster Corps and the manufacturer must cooperate in drawing specifications for vehicles that are not only satisfactory to all concerned, but that can be produced economically. That is as difficult as dividing two doughnuts between three hungry kids. For example, the Cavalry might desire a 2 1/2 – ton cargo truck with a top road speed in high gear of forty-five miles per hour, whereas the Field Artillery might want the same general type of vehicle with a top road speed of only thirty-five miles per hour and with a proportionately greater pulling power; or several using arms and services might be satisfied with a certain type of vehicle but one of them might require a special wheel spacing to permit the use of traction devices which are of no particular value to the other users. A compromise between these conflicting desires must be found before a vehicle acceptable to all can be produced.

With the nineteen million dollars that Jones was complaining about, the Army is purchasing approximately 16,000 vehicles of 32 different types. The specifications in the invitations for bids covering each type of vehicle or unit average twenty-five pages, and each page contains about 10 items or a total of approximately 2,500 items in each invitation.

If the specifications call for any basic changes in chassis, the manufacturer, after the complete engineering layouts have been made on paper, must build a hand made model of the proposed vehicle. These models cost about $80,000 each, and not infrequently several models must be made before a satisfactory vehicle is obtained. If the design seems satisfactory, it costs the manufacturer anywhere from half million to a million and half dollars to make the necessary changes in the factory equipment, tools, dies, jigs, etc., in order to roll the vehicle off the delivery line by mass production methods.

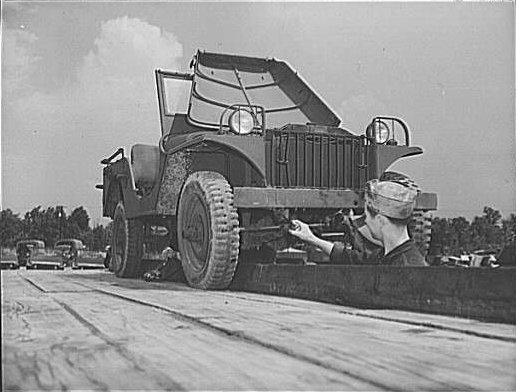

However, before production starts on a vehicle the manufacturer must submit a pilot test model to the Engineering Department at the Holabird Quartermaster Depot. The pilot model is put through a 4,000 mile test that practically amounts to rolling it down the Grand Canyon. Every night when it returns from being run over a washboard road of concrete slabs, or through mud holes, or up hills, the Engineers give it a careful examination, testing and inspecting all the units and assemblies for fractures, leaks, broken parts or similar failures. If anything has gone wrong, the engineers from the manufacturer are called in and they, with the Army Motor Engineers, go over the specifications to correct the fault. After the corrections have been made, and these may run from a weak fuel line connection to complete change in an axle assembly, the pilot model continues under test until the engineers are satisfied that it will perform according to specifications. Not until then does that particular type of vehicle go into production.

However, before production starts on a vehicle the manufacturer must submit a pilot test model to the Engineering Department at the Holabird Quartermaster Depot. The pilot model is put through a 4,000 mile test that practically amounts to rolling it down the Grand Canyon. Every night when it returns from being run over a washboard road of concrete slabs, or through mud holes, or up hills, the Engineers give it a careful examination, testing and inspecting all the units and assemblies for fractures, leaks, broken parts or similar failures. If anything has gone wrong, the engineers from the manufacturer are called in and they, with the Army Motor Engineers, go over the specifications to correct the fault. After the corrections have been made, and these may run from a weak fuel line connection to complete change in an axle assembly, the pilot model continues under test until the engineers are satisfied that it will perform according to specifications. Not until then does that particular type of vehicle go into production.

So you see, Private Jones, what’s involved when you ask to have a truck lifted four inches further off the ground so you can get it out of a mud hole.

“Because of the procurement policy then in force, motor specifications had to be general in nature in order to provide for competitive bidding, and the vehicles so procured were required to be commercial models with only such alternations as would be necessary to conform to the desired military characteristics. The purpose of this War Department policy, of course, was to assure the mass production of trucks in the event of war. At the same time, in the several years before 1940, it had been shown that this procurement policy was having a serious effect upon the Army’s efforts to standardized motor vehicles into a few basic sizes and types.”#

“Precluded by regulations from designing and building its own trucks, the Army’s functions in the development of any new vehicle technically ended with the preparation of the military characteristics by the using arms and the writing of the specifications by the Quartermaster Corps. The automotive engineers of private industry carried on from that point and generally designed, engineered, and built the pilot model in accordance with the stated specifications. The development of a motor vehicle for military purposes therefore had to be somewhat in the nature of a dual enterprise, an attempt to obtain a meeting of minds between the Army, which set forth the characteristics and the specifications, and the automobile industry, which translated them into an acceptable motor vehicle. Patently, collobration and consultation on all aspects of the development, including design and engineering, had to take place constantly between the two if the undertaking was to be crowned a success.

The development of the 1/4-ton was no exception to the above procedure. In speaking of the evolution of the jeep The Quartermaster General himself said: ‘It is a matter of common sense that industry can neither design nor supply the Army’s needs if it does not know them. At the same time, the Army should not attempt to dictate engineering details except insofar as military needs differ from general practice in the industry, or where experience shows normal, standards to be inadequate.’

…It would seem that the Army and the American Bantam Company therefore must share honors for its development. The dispute thus boils down to the somewhat academic question of deciding who did most of the work and who should get most of the credit. Since this was a matter of opinion as well as fact, the evidence advanced by the different groups and persons concerned is often contradictory.” a

Article from Army Motors – May 15, 1940 / Pictures from the National Archives on line.

*from The Jeep – Its Procurement and Development under the Quartermaster Corp, 1940 – 1942, pages 30-33.

#Ibid., page 41-42.

aIbid., page 47-48

So you see, Private Jones, what’s involved when you ask to have a truck lifted four inches further off the ground so you can get it out of a mud hole.

“Because of the procurement policy then in force, motor specifications had to be general in nature in order to provide for competitive bidding, and the vehicles so procured were required to be commercial models with only such alternations as would be necessary to conform to the desired military characteristics. The purpose of this War Department policy, of course, was to assure the mass production of trucks in the event of war. At the same time, in the several years before 1940, it had been shown that this procurement policy was having a serious effect upon the Army’s efforts to standardized motor vehicles into a few basic sizes and types.”#

“Precluded by regulations from designing and building its own trucks, the Army’s functions in the development of any new vehicle technically ended with the preparation of the military characteristics by the using arms and the writing of the specifications by the Quartermaster Corps. The automotive engineers of private industry carried on from that point and generally designed, engineered, and built the pilot model in accordance with the stated specifications. The development of a motor vehicle for military purposes therefore had to be somewhat in the nature of a dual enterprise, an attempt to obtain a meeting of minds between the Army, which set forth the characteristics and the specifications, and the automobile industry, which translated them into an acceptable motor vehicle. Patently, collobration and consultation on all aspects of the development, including design and engineering, had to take place constantly between the two if the undertaking was to be crowned a success.

The development of the 1/4-ton was no exception to the above procedure. In speaking of the evolution of the jeep The Quartermaster General himself said: ‘It is a matter of common sense that industry can neither design nor supply the Army’s needs if it does not know them. At the same time, the Army should not attempt to dictate engineering details except insofar as military needs differ from general practice in the industry, or where experience shows normal, standards to be inadequate.’

…It would seem that the Army and the American Bantam Company therefore must share honors for its development. The dispute thus boils down to the somewhat academic question of deciding who did most of the work and who should get most of the credit. Since this was a matter of opinion as well as fact, the evidence advanced by the different groups and persons concerned is often contradictory.” a

Article from Army Motors – May 15, 1940 / Pictures from the National Archives on line.

*from The Jeep – Its Procurement and Development under the Quartermaster Corp, 1940 – 1942, pages 30-33.

#Ibid., page 41-42.

aIbid., page 47-48